The Athens Cultural Affairs Commission decided to make our public art and public history recommendations to the UGA Presidential Task Force on Race, Ethnicity, and Community an open, public statement. The Task Force is currently taking public comments until October 1, and we encourage you to make your own statements, whether that’s a full endorsement of our recommendations or some ideas of your own.

ACAC’s community of volunteers has spent over 100 hours on this public statement over the past week, based on our own expertise, experience, and observations; eight of us spent Sunday afternoon walking campus. We know that we’re not the main subject matter experts in these specific matters, and we enter this conversation as unapologetic advocates for public art in Athens-Clarke County. Our recommendations build upon and acknowledge decades of effort from faculty, staff, students, community members, and alumni on the issues raised in this article. We enter into this conversation imperfectly but fearlessly.

We hope that a more faithful retelling of the University of Georgia’s history will foster a more welcoming and inclusive student environment, normalize critical community conversations on race and ethnicity, align with a just, 21st Century interpretation of the pillars of the Arch (“wisdom, justice, and moderation”) and the University’s motto (“To teach, to serve and to inquire into the nature of things”), and prevent facile photographic juxtapositions like this one in the national media.

Please join us our inquiry into “the nature of things” as they are now — and in optimism for changing its presumed nature — by endorsing our recommendations, whether in part or in full.

Let’s keep working together — for ourselves, for other students, for the University and its alumni, employees, neighbors.

Summary

The Athens Cultural Affairs Commission (ACAC) urges the University of Georgia’s Presidential Task Force on Race, Ethnicity, and Community to consider the ways in which the three pillars represented in the Arch—wisdom, justice, and moderation—are in direct conflict with the historical markers and public art signifiers on campus. The ACAC asks UGA to examine its corpus of outdoor markers and public art in an effort to update a narrow, exclusionary history plagued by white supremacy and nurture the potential of a greater communal story, as we all share a responsibility to dismantle white supremacy and racism in our community and nation. Using public art and public history to “complicate the narrative” of UGA is a meaningful—and cost-effective—step on that journey. Our recommendations, contextualized and described in more detail below, are $250,000 for three new major public artworks and another $40,000 towards efforts to recontextualize existing historical markers and public artworks. ACAC’s community of volunteers dedicated 100 hours to these recommendations over the past week; we hope that you spend 10-15 minutes reading and reflecting on these ideas.

Introduction

The Athens Cultural Affairs Commission is the volunteer body that makes recommendations on public art and cultural issues to the Athens-Clarke County Mayor and Commission. It has executed important SPLOST- and grant-funded arts projects in Athens-Clarke County (ACC), including the Athens Music Walk of Fame, the Hot Corner Mural, and over 40 new sculptural bus shelters over the past year. As a voice for arts and culture in our community, the ACAC offers several recommendations to the Task Force.

Public art tells us who we are as a community. What we choose to erect in public spaces—whether historical markers, public art, or other forms of recognition—tells us how we see ourselves. Public art reflects a shared history or an imagined future; through a visual language based largely on form, scale, selected physical site, and choice of materials, public art conveys the statement “this is who we are, this is who we were, and this is who we want to be.” Visitors to the University of Georgia—including prospective students and external partners—make inferences about what an institution stands for and whom it values through the public art and markers on its campus.

The recommendations below are additive, not subtractive. We do not propose that UGA remove existing markers or statues but instead provide context to enrich the narratives already there—in bronze, concrete, and granite—to ensure that our community’s prominent historical narratives are not being interpreted predominately through a white supremacist lens.

Public spaces are by their very nature communal, terrains of shared belonging. Public art, in all its forms, encompasses the tangible relics of shared belonging and, more importantly, creates a communal language and shared memory of significant people, events, and values. When monuments and art reflect a one-sided narrative, or one demonstrated to be unjust or immoral, then those with the power to make changes have a public duty to find the courage to let go of the past in order to create a more accurate and more inclusive narrative through art in public spaces.

Review of Public Space

Over the weekend, eight ACAC members and community artists spent an afternoon walking through campus to inform these recommendations.

Examining the corpus of outdoor public art on the University of Georgia’s historic North Campus, the ACAC noticed little diversity in the collection. Most reflect the voices from the dominant white culture. In a four-minute walk from the Arch, through the Chapel Bell, to Old College, students, faculty, staff, alumni, and visitors alike are exposed to the following six historical markers and works of art:

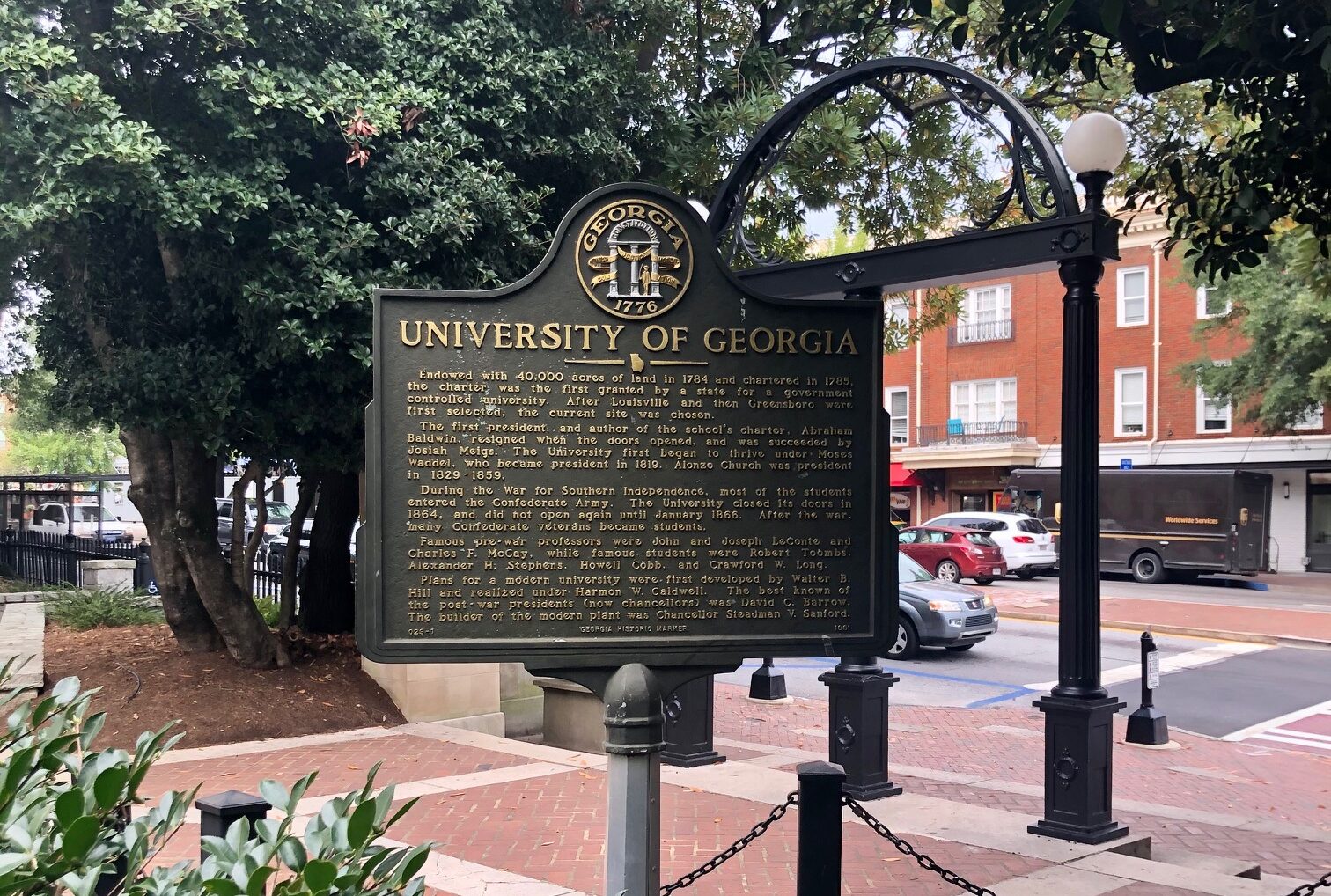

1) University of Georgia Historical Marker (1991): A historical marker for the institution itself celebrates UGA’s Confederate heritage on both its sides: “During the War for Southern Independence, most of the students entered the Confederate Army. The University closed its doors in 1864, and did not open again until January 1866. After the war, many Confederate veterans became students.” The ACAC finds it odd that this marker devotes 20% of its text to the University’s role in the Confederacy, despite UGA’s hundreds of lasting postbellum contributions to the state, the country, and to higher education. The white supremacist phrasing of “War for Southern Independence” aligns with the historically revisionist “Lost Cause” ideology, and the ACAC was astonished to see such language on a prominently sited historical marker erected within arm’s reach of UGA’s most iconic site, the Arch.

2) The Arch (1850s): Erected as the gate for the original iron fence securing campus, easily the most recognized and iconic symbol of the university, the Arch is modeled after the Georgia state seal and features the three pillars of wisdom, justice, and moderation. Considered the “gateway” between the University and the ACC community, it holds an additional 155-year history as a protest site. One of the many documented protests at the Arch includes an 1866 episode when Black Athenian Freedmen demanded that their sons be admitted to the University, 95 years before Black students were finally permitted to attend. White students at the time, most of whom were Confederate veterans, countered the protest, bearing arms. Future UGA Chancellor Patrick Hues Mell, who would later serve as the head of the University from 1878–1888, assured the crowd that the demands of the Freedmen would never be met, and dispersed the African Americans with the threat of a massacre. This moment in local history parallels a theme that would recur in American history. 1866 was a year of violent “race riots,” with whites protesting against the improvement or inclusion of African Americans in their community and culture throughout the former Confederate states. Nearly one hundred years later, in 1961, today celebrated by UGA as the year of desegregation, white student demonstrators hanged a blackface effigy near the Arch and chanted, “Two, four, six, eight, we don’t want to integrate.”

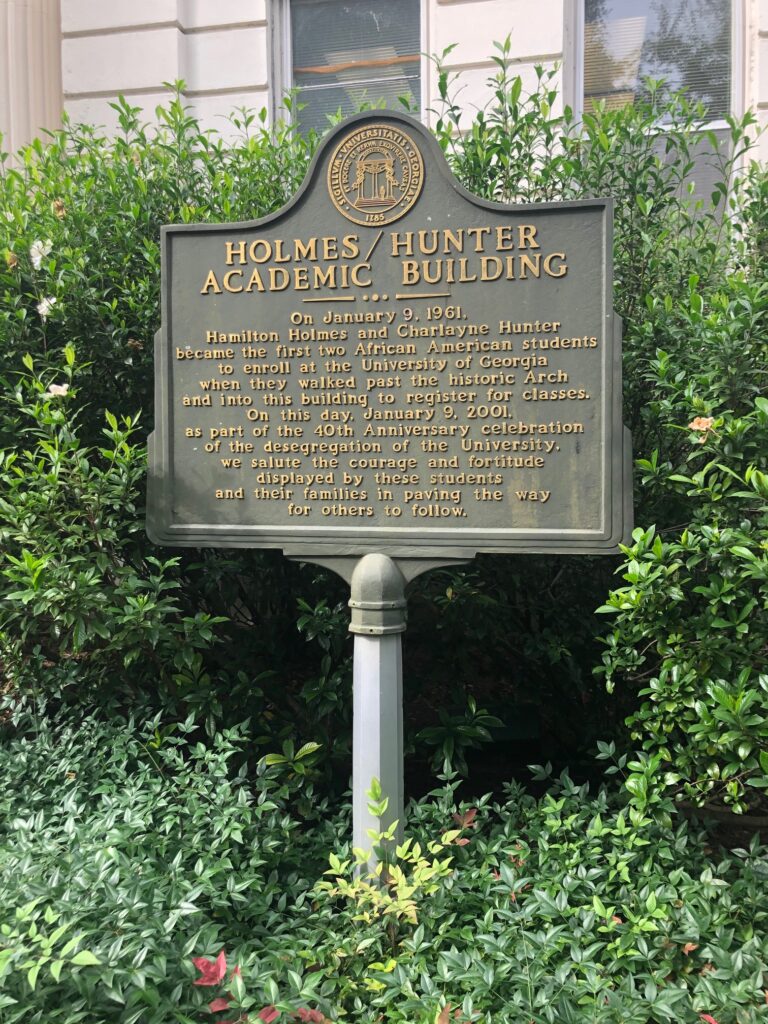

3) The Hunter-Holmes Academic Building (renamed in 2001): This building is named after UGA’s first successful desegregation pioneers, Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton Holmes. In a 2017 Chronicle of Higher Education article about UGA’s connection and disconnection to its own past, Mansur Buffins, a Black student leader, succinctly states, “Right now, as a Black student walking throughout the spaces on this campus, the only time I feel connected to this campus as a physical thing is when I’m passing by the Hunter-Holmes Academic Building.” It’s emotionally important for students, as well as faculty, staff, alumni, and other visitors, to have dedicated non-white spaces throughout campus. Notably, the building’s historical marker is not an official state marker, which sets an important precedent for UGA to act independently to counter official inaccuracies and injustices.

4) Robert Toombs Oak Historical Marker (1987): A historical marker celebrates the Robert Toombs Oak; a “majestic oak once stood” at the spot denoted. Based on hearsay, not historical evidence, this marker for a once-living tree honors the memory of not only the Secretary of State of the Confederacy and a brigadier general in the Confederate army but the same Robert Toombs who was expelled from the University in 1828. It states, “Later, it was said that the tree was struck by lightning on the day Toombs died and never recovered.” The Toombs marker was erected 79 years after the tree’s supposed death, when very few living UGA alumni would have any memory or emotional connection to this oak tree.

5) Chapel Bell Memorial Marker for Pleasant Hull (1951): A bronze plaque, darkened through the years, sits immediately next to the Chapel Bell. It reads in full: “In memory of Pleasant Hull, colorful and traditional bellringer and janitor typical in faithfulness and loyalty of many servants of the university, May 1951.” As Brian Lucear, a Black student leader, wrote in a 2017 Red & Black opinion article about this 70-year-old plaque, “something about these descriptions reached out to me and slashed at my skin, my Black skin.” In 2019, UGA spent $35,500 to repair and restore the Chapel Bell; sadly, the Pleasant Hull marker was not recontextualized in this renovation, and it retains its paternalistic tone despite student protest.

6.) Abraham Baldwin Statue (2011): Abraham Baldwin served not only as the first president of the University of Georgia but also as one of Georgia’s first representatives to the US House of Representatives, serving five terms there before serving another nine years in the US Senate. However, Abraham Baldwin was also one of the signatories at the Constitutional Convention who ratified a fellow signer’s assertion that “South Carolina and Georgia cannot do without slaves,” and he went on to take a strong pro-slavery stance in the writing of the Constitution itself. To ignore Baldwin’s pro-slavery views and his establishment of the University as an all- white institution does not advance a vision of UGA as an inclusive community. The Baldwin statue’s placement, diagonally opposite the Hunter-Holmes Academic Building, is a tension pregnant with possibilities for drawing wisdom from an acknowledgement of the past and inspiring hope for a better future.

The Baldwin statue is just the most recent of these examples of public art that begs for a fuller, more truthful context. We know that the State enacts and designs historical markers (the 1991 University of Georgia Historical Marker; the 1987 Roberts Toombs Oak Historical Marker), but we encourage the University to exert its own power, influence, and finances to recontextualize these, as it did with its own Hunter-Holmes historical marker.

When UGA’s POC students talk about the microaggressions they experience in UGA campus life, many of the markers of North Campus, propagated by the University itself, literally codify them in stone. As a result, we find much of UGA’s public art and historical signifiers to be unwise, unjust, and immoderate—directly contradicting the Arch’s fundamental pillars.

Recommendations

The ACAC urges UGA to act with the same “faithfulness and loyalty” it ascribes to Mr. Hull on its Chapel Bell memorial marker as it considers our proposal. We offer the following recommendations to the University of Georgia Presidential Task Force on Race, Ethnicity, and Community:

1.) The Task Force to allocate $250,000 to initiate three new works of public art on campus that offer a “counter-narrative” to the University’s current exclusively white-dominated corpus of outdoor public art, many of which feature white supremacists. This budget will allow for two major sculptural works ($100,000 each) and a significant mural, and all budgets should be significant enough to attract proposals from major artists from across the United States and, perhaps, the world.

2.) Commit an additional $40,000 to provide historical context to many of the University’s current historical markers to ensure that the University of Georgia no longer enshrines revisionist history, seen solely from the vantage point of the “dominant” white culture, on its campus.

3.) The ACAC recommends that UGA allocate funds for proper siting and landscaping for any new public art projects, replicating the care and attention taken with the physical environment immediately surrounding the Baldwin bronze.

Our recommendations align with the Task Force’s five main strategies:

Build Community

More historically accurate public art will foster vital community conversations on race. Over time these new pieces of public art will help to “normalize” such conversations. Further, our recommendations urge the University to take strong first steps to fully acknowledge the multiple communities that have played vital roles in building Georgia’s flagship university. Not being legally allowed on campus is still a painful, living memory for many Athenians.

UGA’s own Policy on Public Sculpture and Environmental Artworks states that “this campus is an especially suitable location for carefully sited works of outdoor art which celebrate and commemorate the spirit of the time.” We hope that this Task Force can lean into “the spirit of [this] time” and develop more inclusive and historically accurate public artworks and policies.

Elevate People

Since this strategy directly refers to “student recruitment and retention efforts,” we propose that these new artworks be incorporated into the thousands of UGA walking tours hosted by the University each year as one of its primary recruitment tools.

Develop Leaders

Increased cultural competency is just one expected outcome of these public art recommendations. Cultural competency is a vital leadership skill that current UGA students demand from their future employers and should expect from their alma mater.

Increasing Funding

Future giving to diversity initiatives can be stewarded through appropriate public art and naming recognition. Once UGA makes its own institutional commitment to an accurate portrayal of its accomplishments in its public spaces, UGA Alumni affinity groups can encourage giving through a variety of annual giving campaigns, similar to numerous departmental brick campaigns, the renaming of the Mary Frances Early College of Education, the College of Veterinary Medicine memorial garden, and event registration fees with baked-in gift components. Major donors may be interested in blended gifts that support a diversity initiative with an element of public art, and corporate partners will appreciate a campus that is visually forward-thinking in its stance on inclusion.

Engage Alumni

Public art inspires pride in a shared experience. With each commencement, UGA’s alumni population looks less like the people it has chosen to celebrate on campus. A public space that accurately reflects the university community will inspire alumni to reconnect. UGA alumni chapters and affinity groups can leverage this initiative because it honestly portrays a diversity-embracing university experience. Peer and aspirant institutions have found public art to be an effective alumni engagement tool.

Recent University Public Art Precedents and Lessons Learned

Abraham Baldwin Statue

The public knows a great deal about why UGA pursued the placement of a statue of Abraham Baldwin on North Campus, installed in 2011. The University told its own story effectively in a 2009 UGA Today article.

From the article, entitled “The Story of the Statue: And How It Was Decided to Build a Tribute to Founder Abraham Baldwin,” we know the Abraham Baldwin statue was the concept of Loch Johnson, Regents Professor of Public and International Affairs, meant to “preserve a link to the past and serve as a unifying force for university faculty, staff and students.”

The article identified the future location of the statue, on North Campus adjacent to Old College and was specific about the work’s funding sources: “Funding for the statue will come from private donations and will be guaranteed by a $60,000 matching grant through the UGA Alumni Association.” UGA formed a committee to select an artist for the statue, which would make its debut during the University’s 225th anniversary in 2010. The article highlighted Baldwin’s five terms in the US House of Representatives, his nine years in the US Senate, and his conferral with James Madison at the Constitutional Convention in 1787.

While transparent about the budget and process, the article avoided mention of Baldwin’s many pro-slavery views. This historical fact was no secret when the Baldwin statue was being planned. UGA, a Predominately White Institution (PWI) which itself directly benefited from enslavement, nonetheless proclaimed his relevance as a link to the past and a unifying force for the campus community.

If UGA is to move toward more inclusive and historically faithful public spaces that build a more inclusive community and culture, it cannot feign ignorance of Baldwin’s pro-slavery efforts. To omit these salient points from his history does not advance the University’s mission to inquire into our shared heritage.

Baldwin Hall Memorial

The Baldwin Hall Memorial demonstrates a missed opportunity to address the duplicity of prior campus public art initiatives: a space that looks and feels rushed and insignificant, planned more as an asterisk to the history of the building and less as a significant memorialization to atone for the past. It contrasts starkly with the Baldwin statue, both in transparency as well as the aesthetics of the processes that created them. Though the narrative of granite sourced from a local African American-owned quarry is meaningful and commendable, the Baldwin Hall Memorial was an effort unequal to commemorating a site that bore witness to the gravity and inhumanity of slavery associated with UGA’s history.

If the Baldwin Hall Memorial was intended to lead to “a broader discussion” of the University’s role in enslavement, then we hope that this Task Force will devote some of its budget to opening the conversation through public art with more sincerity, creativity, sensitivity, and input from our local communities of experts. It is confounding to us that UGA excluded so many faculty—subject matter experts in public art, history, and inclusive language—from its Baldwin Hall Memorial Committee. The University should pride itself in its diversity of thought from bodies like the Institute for African American Studies, the Lamar Dodd School of Art, Franklin College’s Department of History, the Georgia Museum of Art, and the Center for Social Justice, Human and Civil Rights. Instead, UGA seemed afraid of its own expertise.

Should this Task Force on Race, Ethnicity, and Community choose to implement the recommendations of the ACAC, care must be taken to avoid repetition of these recent mistakes. The risks to UGA’s future, by not using more inclusive procedures and a more honest acknowledgement of its history—when creating public art and other cultural signifiers—are far greater than any short-term negative publicity about its past. Its efforts to redress historic injustices through public art will look and feel as drab as the Baldwin Hall Memorial, and its language will be interpreted as insincere, as overly cautious, and as bureaucratic as the Baldwin Hall Memorial’s text: Phrases like “most likely slaves or former slaves” and “upon guidance of the state of Georgia, they were reinterred at the Oconee Hill Cemetery” are inadequate summaries completely lacking in empathy for the atrocity committed upon the remains of our communal ancestors.

Community Engagement and Matching Gifts

We recommend that the Task Force fully engage the UGA and Athens community of experts to thoughtfully, creatively, and artfully enact these recommendations. The recent examples of the University’s processes, in terms of budget and decision-making, cited above, offer lessons to learn and missteps to avoid.

The ACAC is confident in our recommended allocation of $290,000 toward these construction and modification efforts for public art on campus. Since the Athens Cultural Affairs Commission completed its Hot Corner Mural in 2019, we have seen multiple instances of UGA using the mural as a photographic backdrop promoting the community of Athens. We hope to inspire UGA to use its own funds to create its own mural in a prominent location, building on UGA’s powerful murals dating to the early 1940s; as with its past, we want UGA to consider mural-making an important part of its present and future. The cost of the Hot Corner mural—including artist fees for an internationally renowned muralist who has worked on five continents, a local muralist who played a major role in its timely completion, rental fees for two sets of scissor lifts, travel, in-kind support, and various other expenses—came in under $40,000, including a $15,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. In comparison, the ACAC’s 2019 Hot Corner Mural budget was nearly identical to UGA’s 2019 Chapel Bell restoration costs.

The ACAC has learned much from its own mistakes. Not until the Hot Corner Mural’s successful execution did our art projects fully engage all of Athens. The mural was a tipping point for our organization; over 40 muralists submitted proposals for the mural and 30 Athenians were involved in the selection process, with all participants having an equal voice and an equal vote.

The completion of the Hot Corner Mural earned the ACAC a level of buy-in and respect from the ACC Mayor and Commission that it had never before attained. More importantly, this prominent piece of artwork fostered conversations about the use of public space downtown. Within three months of the mural’s creation, the local government approved a proposal to turn the parking lot which the Hot Corner Mural overlooks into downtown’s first pocket park. Within nine months, the ACC Mayor and Commission approved ACAC’s budget proposal for a full-time position devoted to public art in ACC, set to begin in 2021.

Community members tell us that this mural makes them feel “seen,” and the mural itself fulfills its goal as a tribute to Hot Corner: a historic African American locus of commerce, culture, and entrepreneurship. Public art at UGA can galvanize similar conversations all over campus. It holds the promise of normalizing conversations about race, enhancing UGA’s cultural competencies, creating more spaces that resonate with more students, and winning the applause of students, employees, and alumni, eager to donate towards even more public art.

To signal my sincerity and commitment to supporting this effort, in my capacity as an alumnus, arts advocate, and community member, I (Andrew Salinas) will personally donate a month’s salary, so long as ACAC is promised a seat at the table and UGA includes its own subject-matter experts in these efforts. If these recommendations are fully implemented, I’ll encourage other alumni to do the same. If we can convince five senior UGA administrators to make the same commitment, we could easily pay for one of these major public artworks outright.

Closing

In summary, we urge the Task Force to allocate $250,000 to create three major works of public art that provide a more truthful retelling of the University’s historical connections to white supremacy now on display in its corpus of public art, much created long before African Americans were allowed on campus as students or faculty. We urge UGA to take these actions

for itself, its students, its alumni, its employees, our neighbors, and the greater good.

Furthermore, we recommend that the Task Force allocate an additional $40,000 to revise or complement the texts of existing historical markers to provide a more inclusive and more accurate portrayal of the people and events which shaped the University.

We have to point out that the same day ACAC members walked campus to perform a “close reading” of historical and artistic University signifiers, a story broke about Greek life at UGA: “A fraternity at the University of Georgia self-suspended after images from a group chat revealed the students using racist, sexist and homophobic language,” the Washington Post caption reads. The image captioned has the Arch in the background with the full text of the UGA historical marker readable: “During the War of Southern Independence, most of the students entered the Confederate Army…” Once we commit to these recommendations, these juxtapositions won’t be so facile.

This Task Force represents an intentional shift in institutional focus, and UGA can appropriately address its history of decades of direct participation and profiteering in enslavement, neighborhood displacement, active racism, segregation, benign neglect, and active historical erasure. The question before the Task Force is how the institution chooses to use its public art. Will it continue to avoid an honest avowal of its past, or will it seek reconciliation by opening up to new dialogues that bridge the pain and injustices of the past? Public art is the means to both. UGA has the power to choose how to frame its own past and decide whether it has the wisdom, justice, and moderation that the Arch calls for.

Sincerely,

Andrew Salinas, Chair

On behalf of the Athens Cultural Affairs Commission

The juxtaposition of the University of Georgia Historical Marker and its fabled Arch, the most prominent and mythologized public artwork on campus, makes for an unwelcoming official entrance to North Campus.

This marker, not official state signage, represents an important precedent for these recommendations: the University has made its own markers before outside of a state legislative process. UGA had the political will to make its own marker then, and we urge UGA to use its own precedent and power to enact our recommendations here.

We request that UGA enact our recommendations with a greater reverence and better historical accuracy than this marker, erected 79 years after the oak’s death.

Last year’s $35,500 renovation of the Chapel Bell was the perfect opportunity to re-contexualize this paternalistic plaque within arm’s reach of the Bell. The next best opportunity is through the recommendations of this Task Force.

The Abraham Baldwin state begs for re-contextualization and more historically faithful public art in its own sightline, where campus meets community.

After writing our public statement, we received a response to our Open Records Request for Baldwin Hall Memorial costs: $104,880 for “cutting/polishing the raw granite, drilling the fountain granite pieces, transporting to campus for placement at the site, and installation… Please note that does NOT include the value of the granite material, which was donated to the University.” While ACAC finds that the Memorial “looks and feels rushed and insignificant,” we can now definitely say that this was not an inexpensive project, particularly when considering its significant material costs were donated. Based on this new information from UGA’s most recent precedent, we’d like to revise upward our budget recommendations in this statement.